By Subodh Varma, TNN

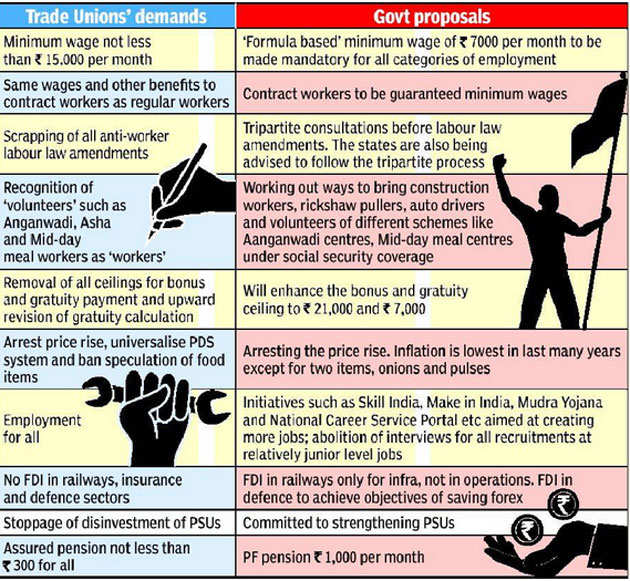

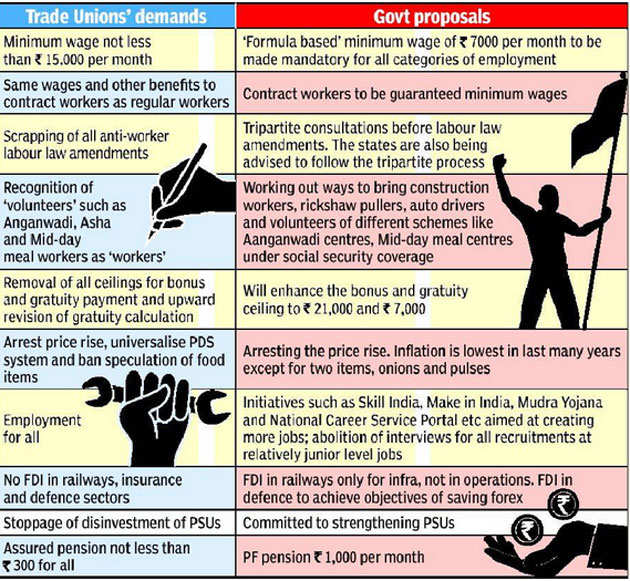

One of the key issues on which the negotiations between the government

and the 10 central trade unions that had called for a general strike on

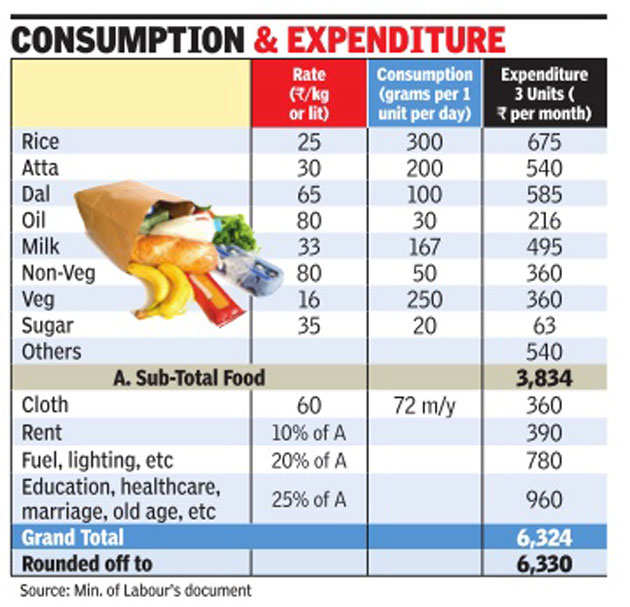

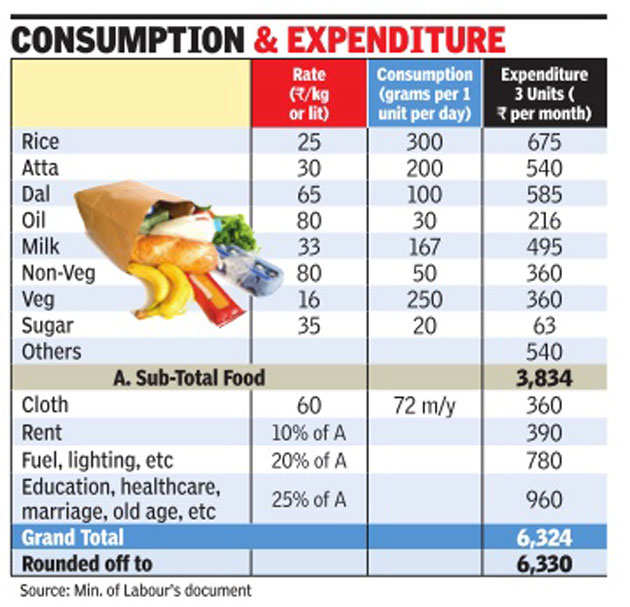

Wednesday broke down was that of minimum wages. A labour ministry

document circulated amongst the trade unions days before the strike,

argued that by current norms, prices and calorific needs, Rs.6330 per

month is the monthly wage adequate for an unskilled worker with a wife

and two small children.

The trade unions and various other federations that represent 15 crore

workers had demanded Rs.15,000 per month minimum wage as a national

level floor wage. Striking a generous posture, the government modestly

increased its proposal to Rs.7098 per month.

What the government had proposed was less than half of what was

demanded. This was one of the contributory factors to the breakdown of

negotiations. Other demands of the workers included social security

coverage, non-interference with existing labour laws, etc.

How did the government calculate their proposal? A look at the fine

print shows a slew of gross under-estimations and the use of an archaic

formula first spelled out way back in 1957. Some of the food items'

prices are far from reality. For instance dal is costed at Rs.65 but

only one of the various dals in the market - chana or gram dal - comes

in this range. Arhar (tur) is Rs.135 per kg, urad is Rs.117.5, masur is

Rs.95. All these current retail prices are from the consumer affairs

ministry's price monitoring data spanning 81 cities and towns.

Mutton is priced at a bizarre Rs.80 per kg, although it doesn't really

matter because only 50 g is allowed. This is convertible to 250 grams of

vegetables which are priced at an imaginary Rs.16 per kg. In the real

world mutton is selling at anywhere between Rs.300 to Rs.400 per kg. And

rarely if any vegetable sells at Rs.16 per kg.

But the real rub comes in the non-food items. Just Rs.390 is supposed to

be spent on rent every month. And, fuel for cooking and utilities like

electricity etc. are all supposed to be covered under a meagre Rs.780.

All education, medical expenses, marriages, care of elderly, recreation

etc. is lumped together and costed at 25 percent of the food

expenditure. This practice started after the Supreme Court in a landmark

judgement in 1991 directed as much saying that if such a minimum wage

cannot be guaranteed then the managements have no right to run their

business. But even this works out to a mere Rs.980 per month.

Costs of education and healthcare have risen tremendously in the past

several years and even one major episode of sickness in the family would

be devastating. The government's wage calculation seems to be

blissfully unaware of this.

Recent government data shows that real wages, that is, after adjusting

for inflation are dipping while the share of wages to profits is also

dipping in the organized sector. In the unorganized sector which employs

over 90 percent of India's workforce, wages are abysmally low and

conditions of work onerous. Small wonder then that the trade unions were

unwilling to accept the government's proposals.

Source : The Economic Times